Posted by Tim Irwin

The nineteenth century saw a revolution in the publication of fiscal information and other government data. As Ian Hacking has observed, “If there is a contrast in point of official statistics between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it is that the former feared to reveal, while the latter loved to publish” (p. 20). Yet some governments today make their nineteenth-century counterparts seem like shrinking violets—the new openness being symbolized by the remodeled German parliament shown above, whose glass cupola was designed to show that parliament was “transparent, its activities open to view” (see Alasdair Roberts, Blacked Out, p. xii).

The earlier revolution was discussed in two previous posts on this blog (here and here). This post investigates the changes of the late twentieth century.

The early years of this revolution are nicely illustrated in the episode “Open Government” of the British TV series Yes Minister,[1] which screened in 1980 when the UK government published its budget and accounts, but was not nearly as open as it is now. A new government has just been elected and the incoming Minister of Administrative Affairs meets the Permanent Secretary of his department. It transpires that they have met before when the Minister, in opposition, gave the PS “a grilling over the Estimates in the Public Accounts Committee.”

“Opposition’s about asking awkward questions,” the Minister says.

“Yes, and government is about not answering them,” replies the PS.

“But you answered all my questions, didn’t you?” asks the Minister.

“I’m glad you thought so,” says the PS.

Later in the program, the Minister warns the PS that the new administration will be less secretive than the last. To the Minister’s surprise, the PS has anticipated his wishes: the Department is already preparing a White Paper entitled “Open Government.” But the PS later confesses to his colleagues that the White Paper is called “Open Government” only because “you always dispose of the difficult bit in the title” and notes that the less you intend to do about something the more you have to talk about it. Another PS claims that open government is a contradiction in terms: you can be open or you can have government.

The Rise of Open Government

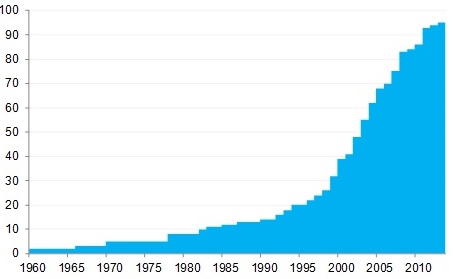

Since 1980, however, governments have become much more open. At that time, only 8 countries had right-to-information laws. Now, 95 do. (The UK’s law, for example, dates from 2000.)

Number of Countries with a Right-to-Information Law, 1960–2013

Source: , using data created by and .

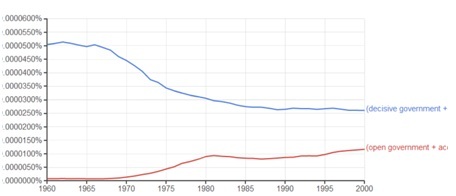

Google’s Ngram Viewer also gives a sense of how thinking in the English-speaking world has changed. It shows that from about 1970 people started writing more often about open government, accountable government, and transparent government, and less often about decisive government, strong government, and efficient government.

Frequency of Open Government, Decisive Government, and Related Wordsin Books Digitized by Google, 1960–2000

Source: . Note: The higher, blue line show the sum of the frequencies of decisive government, strong government, and efficient government. The lower, red line shows the sum of the frequencies of open government, accountable government, and transparent government (case-sensitive). Smoothing of 3 is used.

The Rise of Fiscal Transparency

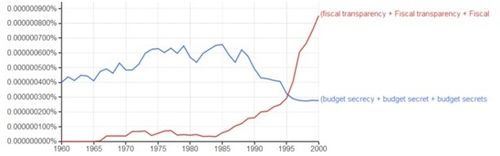

Although there is no index of fiscal transparency that goes back to the twentieth century, it is clear that the trend toward open government has affected public finances. Some case studies of recent changes are available in Open Budgets, a book edited by Sanjeev Khagram, Paolo de Renzio, and Archon Fung. Quantitative evidence of a change in thinking comes again from Google’s Ngram Viewer, which shows that the expression fiscal transparency started to become popular in the mid-1980s, while budget secrecy was used relatively more in the 1970s and 1980s, and seems less on people’s minds now, perhaps because much more budgetary data are published.

Frequency of Fiscal Transparency and Budget Secrecy in Books Digitized by Google, 1960–2000

Source: . Note: The underlying search is case-sensitive. The initially higher, blue line shows the sum of the frequencies of budget secrecy and variants as Budget secrecy and budget secrets. The initially lower, red line shows the sum of the frequencies of fiscal transparency and variants in different cases. Google’s default smoothing of 3 is used.

Possible Causes

What caused the rise of open government and of fiscal transparency in particular?

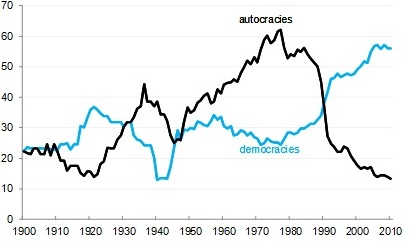

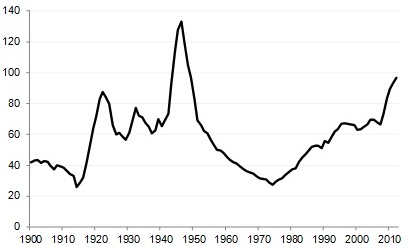

These days, democracies tend to be more open than autocracies, as shown by Joachim Wehner and Paolo de Renzio, and one possible cause of increasing openness was the rise of democracy. During the middle of the twentieth century, autocracy was a common form of government, but from the late-1970s the proportion of autocracies in the world started to decline, while the proportion of democracies started to increase.

Democracies and Autocracies as a Percentage of Total Number of Countries, 1900–2010

Source: Center for Systemic Peace, Polity IV database, available here.

Note: The definitions of democracy and autocracy are those of the Center for Systemic Peace. The percentages do not sum to 100 because there is a third group of countries (“anocracies”) that are classified as neither democracies nor autocracies.

Although some twentieth-century autocratic governments published their budgets and accounts, the political thinking with which they were associated placed little value on open and accountable government. For instance, Carl Schmitt, the conservative German political theorist wrote disparagingly in 1923 of the claims nineteenth-century liberals made for openness: “The elimination of secret politics,” he said, had become for them “a wonder cure for every kind of political disease” (The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy, p. 38). By contrast, Karl Popper’s influential critique of autocracy published in 1945, The Open Society and Its Enemies, stressed the value of critical debate.

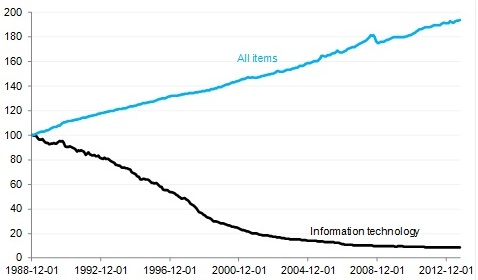

A second possible cause of increasing openness was the improvement in information technology, which has made it much easier to create and publish information about public finances and other matters. The following chart shows how the price of information technology (hardware and software) has fallen in the United States since 1988. Similar changes have occurred around the world, and probably predated 1988, the first year in which this data series on IT prices is available.

Consumer Price Indexes in the United States for Information Technology and All Items

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, FRED Economic Data series. For details, see here.

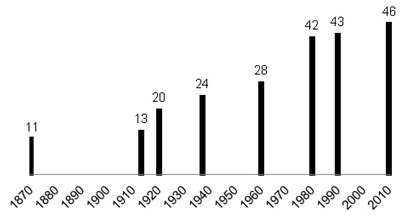

A third possible cause of increasing openness and fiscal transparency was the growth of government. In 1920, government spending in advanced economies amounted to about 20 percent of GDP. By 1980, it had more than doubled, making public finances much more important. Public debt, after falling sharply after the Second World War, also began to pick up again in the early 1970s, giving creditors more reason to scrutinize public finances.

Government Spending in Advanced Economies as a Percentage of GDP, 1870–2010

Source: Vito Tanzi and Ludger Schuknecht, , 2000, Table I.1, p. 6, except for the figure for 2010, which is from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database. Note: data are unweighted averages of the spending of general government in Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States.

Public Debt in Advanced Economies as a Percentage of GDP, 1900–2012

Source: IMF’s .

Note: The data are averages, weighted by GDP at purchasing-power parity, for countries classified by the IMF in 2012 as advanced economies.

Like the nineteenth-century revolution in transparency, the late-twentieth-century revolution has not lived up to everyone’s expectations. Many question whether right-to-information laws have made it too hard for governments to deliberate effectively, out of the glare of the news media. And others question whether the enormous volume of public information has genuinely increased public understanding of policy issues. Are public finances encapsulated in a simple set of financial statements that include good measures of the deficit and debt (see this IMF policy paper)? Is there a plain-language citizens’ budget? And are there journalists, think tanks, and independent government agencies that evaluate the reports and intelligently criticize the government’s plans and performance, cutting through the detail to pick out the key elements and trends?

[1]Yes Minister is available in print as The Complete Yes Minister: Diaries of a Cabinet Minister by the Right Hon. James Hacker MP, ed. Jonathan Lynn and Antony Jay (Salem House) 1987 (see pp. 14, 21).

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.