Posted by Marie Laure Berbach, Grégoire Rota Graziosi, Mousse Sow and Benoit Taiclet[1]

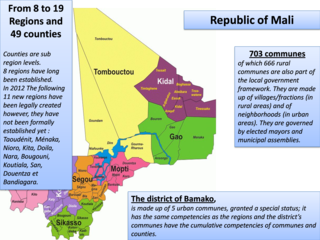

The peace agreement settled with northern Mali insurgents in 2015 includes a large fiscal decentralization component. This reform involves the scaling up of local governments’ resources by up to one third of the country’s budgetary revenue, thus tripling local budgets within three or four years, and increasing the number of sub-national regions from 8 to 19 (two of which are desert lands).

A Bold Move to Boost Local Development and Foster Peace

The long-established process for a three-tier decentralization in Mali (e.g. communes, counties and regions) has delivered mixed results over the years. The communes have proved pivotal in providing basic services in the education and health sectors, and in initiating local development projects. Nevertheless, local governments have suffered from insufficient financial and human resources, as well as limited support from central government agencies, which has constrained local development. In 2013, after decades of slow growth and limited poverty-reduction, and two years of armed insurgency and political instability, the issue of decentralization became the center of heated debate within the peace talks held in Algiers to restore peace in the Northern Mali hinterland.

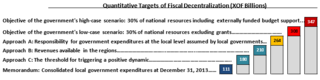

The Malian administration is envisaging deepening decentralization through a new “regionalization” initiative designed to boost local economies. This plan involves redrawing the country’s administrative map and scaling up fiscal transfers to local governments to the tune of one-third of the country’s budgetary revenue (see chart below). In this context, the objective is to: (i) double or triple local budgets (depending on the option chosen) within three or four years, (ii) increase the number of regions from 8 to 19 and redeploy counties accordingly, and (iii) consolidate budgets at the communal level.

Ambitions and Risks Ahead

This radical reform of local government structures and finance is the first since 1992 when regions were first established. The “regionalization” phase of the reform comes with tight deadlines, which will be challenging to meet during a period when local populations are healing their wounds from the civil war, infrastructures have been severely degraded, and pervasively poor financial governance remains an issue. If not properly implemented, regionalization entails several risks:

- If the new regions’ governance framework is poorly defined and ill-implemented, local management will result in an unsuitable and inefficient use of resources.

- If transfers to local governments are inadequately estimated, insufficient and unpredictable revenue flows to local budgets will lead to ineffective local policies with little positive economic and social impact, and potentially a loss of control of local finances and debts.

- If the transfer of competencies and related resources are unsuited to local needs, it could increase local inequities, deplete the central government budget, and yet not foster growth and development.

Technical Assistance Provided by FAD

On October 22, 2015, following requests by the Malian authorities for FAD to help adapt the fiscal framework to the new regionalization framework, two related TA reports by FAD on fiscal decentralization and local taxation were presented at the International Conference for the Economic Recovery and Development of Mali in Paris. The reports were published and are available on the IMF Website and on the OECD Website. Issues covered by the reports include the following:

- The need to build consistent and sustainable local governments with particular attention to the regional level, which are best suited to handle funds and implement large-scale development projects.

- Optimization of local taxation (although it will not alone cover all needs) keeping in mind that domestic (central) tax revenue mobilization remains a high priority by suppressing some obsolete local taxes, establishing a synthetic final tax on small businesses, improving taxation on property value, and replacing some specific local taxes by various user fees.

- Introduction of an efficient and equitable (suited to needs, transparent and sustainable) system for sharing central government VAT revenues.

- The establishment of good financial governance through strong accountability, central government support, and capacity building for local officials

[1] Marie Laure Berbach is a magistrate from France’s “Cour des comptes” (Supreme Audit Institution), and a well-known expert in fiscal decentralization, currently working with FAD on Mali and Senegal.

Gregoire Rota Graciozi was an FAD senior economist in the tax policy division. In 2015, he moved back from the IMF to his home country. He is now a professor in CERDI-CNRS (University of Auvergne, France).

Mousse Sow is an FAD Fiscal Economist, and coauthor of a paper on Fiscal Decentralization and the Efficiency of Public Service Delivery.

Benoit Taiclet is an FAD Senior Economist, and a former civil servant from the French Ministry of Finance; he has led a number of successful TA missions in sub-Saharan countries.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.