Posted by Richard Allen and Miguel Alves[1]

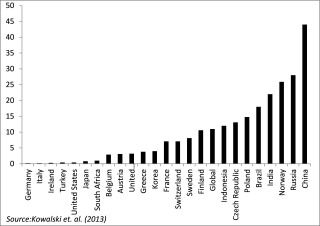

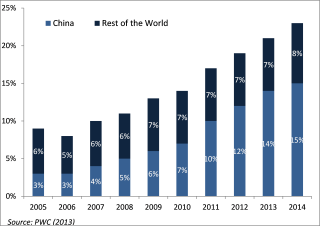

Why should policy makers worry about the performance of public corporations (PCs)? One reason is that, despite the large-scale privatizations that began in the 1980s, companies owned or controlled by the government continue to account for a large share of economic activity, and of public assets and liabilities (see charts below). Many PCs are pressured or mandated into fulfill political objectives and engage in public service obligations and other quasi-fiscal activities (QFAs) for which they are not compensated. PCs may also be used as a mechanism for circumventing traditional fiscal controls and as a conduit for financial corruption. (click to enhance images)

Chart 1. Market Capitalization of Listed PCs (in percent of GNI) | Chart 2. PCs as a Percentage of Global 500 |

|  |

Second, many studies have highlighted how failures of PCs can result in huge economic and fiscal costs. One recent study[2], for example, analyzed a series of episodes in which contingent liabilities materialized over the period 1990-2014. It concluded that the maximum cost of those episodes involving PCs was 15.1 percent of GDP, and the average cost was 3 percent of GDP. PCs were the second largest category of fiscal risk after the financial sector (which includes many state-controlled companies). Moreover, the number of episodes involving PCs, as well as their average fiscal, cost doubled between the 1990s and the 2000s.

Third, around the world, the structure and characteristics of PCs have been changing, as the companies take on a more strategically important role. Traditionally, many PCs were natural monopolies. However, as a result of technological changes and competitive forces, natural monopolies in sectors such as electricity distribution and telecommunications have disappeared. Many of the largest PCs now operate in the oil, gas, copper and other mineral sectors, and some are only legal monopolies rather than natural monopolies.

To address these concerns, a new paper published by the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department[3] sets out a framework for the better financial oversight of PCs Key points are as follows:

- The definition and classification of PCs and other public entities should be clear, transparent and consistent with the IMF’s Government Finance Statistics Manual 2014 (GFSM 2014). Many countries, however, do not define PCs clearly, nor distinguish them from government agencies (e.g., regulatory bodies) that undertake purely non-commercial activities, and create no significant fiscal risks.

- Governments should carry out a full assessment of the costs and benefits of new proposals to establish a new PC. They should also review periodically the economic and social viability of existing PCs, and consider whether they might be closed down, converted into a noncommercial government entity, or privatized.

- Governments should publish a clear statement regarding their role as owners of PCs, and the financial, economic, and social policy objectives they are trying to achieve.

- Many countries have found it helpful to prepare a separate legal framework for PCs, in addition to these entities’ obligations under company law. This framework should define the role of sector ministries that “sponsor” PCs, as well as those of the finance ministry, and the entities’ management boards. Legally enforceable sanctions may be necessary to meet financial or operational performance targets, financial distress or insolvency, or serious cases of fraud and financial mismanagement.

- Some countries have chosen to locate both the ownership and financial oversight functions in a central agency, often the finance ministry or the president’s office. Other countries apply a decentralized ownership model in which ownership is vested in a holding company or investment company.

- Analyzing the financial performance of PCs requires specialized and advanced skills which in many countries are located in a dedicated oversight unit of that is often located in the finance ministry (e.g., Chile, France, New Zealand, South Africa, and Sweden), the prime minister’s office (Finland), or the ministry of planning (Brazil).

- The tasks of the oversight unit include analyzing the financial plans of PCs, setting appropriate financial targets (e.g., profit margins, returns on equity, exposure to internal or external fiscal risks), monitoring performance against quarterly and annual financial reports, and assessing the cost and impact of QFAs. These units frequently publish annual monitoring reports on the financial and operational performance of PCs and the risks they create. The note discusses the optimal structure of such reports, providing links to several good examples.

- PCs should ideally follow international standards of financial reporting (IFRS) and audit. In countries that lack skills and capacity, it may make sense to focus such a policy on only the largest PCs, or those that can create more substantial fiscal risks.

- The cost of delivering QFAs should be fully funded through the budget and disclosed separately in the financial statements of both the government and the PC. The “How To” Note provides some illustrations of how to estimate the cost of QFAs.

Finally, advanced countries have spent many years building and refining the oversight systems described in the paper. It may not be practical to implement such ambitious reforms in low-capacity countries. In such cases, a risk-based approach to building an oversight regime for PCs is strongly recommended. The note provides a checklist of the main elements of such a regime and how they might be sequenced.

[1] Richard Allen is a Visiting Scholar to the IMF, and co-editor of the PFM Blog; Miguel Alves is a Senior Economist with the Fiscal Affairs Department of the IMF.

[2] Bova, E., M. Ruiz-Arranz, F. Toscana, and H. Elif Ture, 2016, “The Fiscal Costs of Contingent Liabilities: A New Dataset,” IMF Working Paper, WP/16/14.

[3] Richard Allen and Miguel Alves ”How to Improve the Financial Oversight of Public Corporations”, IMF, Fiscal Affairs Department, How To Notes No. 5, November 2016.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.