Posted by Andrew Bauer and David Mihalyi1

Countries rich in oil and minerals commonly use sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) to store a share of their natural resource wealth. Examples include Chile, Kuwait, Norway, Texas (U.S.), Timor-Leste, and more than 50 other countries. These funds have been used to decrease budget volatility, save for future generations, or earmark financial earnings for education or infrastructure spending.

But over the last decade we have seen a new trend: governments creating funds when resource revenues are small, distant, or uncertain. This is yet another manifestation of the "presource curse" where the discovery of oil, gas, or minerals leads to rosy expectations and over-optimism from governments, citizens and international institutions, leading in some cases to an unsustainable spending boom and institutional upheaval.

International advisors—especially some economists at international institutions, investment bankers, and lawyers—have promoted the creation of what we call “premature funds.” Yet there are considerable costs and risks associated with their establishment, and uncertain benefits.

Risk 1. Saving while borrowing

In many countries—especially those with fiscal revenues that are large relative to the size of their population or economy—it makes sense to set aside a portion of oil or mineral wealth. A government can earn interest on these savings. For instance, the Texas fund earmarks its earnings for public universities; Alaska uses its earnings to distribute cash to each resident; and Norway and Timor-Leste use their funds to finance their budgets. However, this approach makes less sense where the government has a large stock of public debt to repay.

For example, Ghana’s transparent and conservatively-managed funds have yielded a net return of around 1 percent annually since they were established in 2011. However, over the same period, the country has borrowed over USD 3 billion in Eurobonds and is paying more than 9 percent interest on its latest Eurobond issuance.

Similarly, Mongolia has invested the money in its Fiscal Stability Fund with Mongolian commercial banks that generally pay 7 to 9 percent interest in domestic currency. In contrast, the government is paying 14 percent on short-term domestic debt and nearly 6 percent on its latest Eurobond issuances. Interest payments on Mongolian public debt alone were greater than USD 400 million in 2016, more than the government spent on healthcare for the whole country.

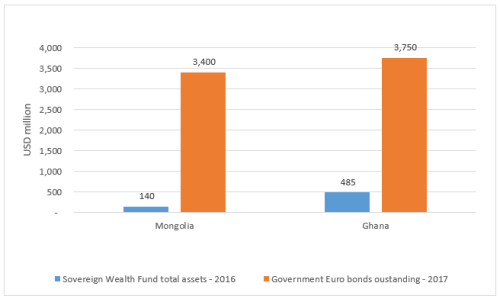

Both examples highlight the risk of borrowing extensively at high interest rates, while earning low returns on an SWF (see chart below). The overall impact of savings is a net loss running into many millions of dollars (especially to foreign creditors). The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guyana and Lebanon, all highly indebted countries, are also at an advanced stage of establishing oil, gas or mineral funds.

Savings and external commercial debt accumulated by the governments of Ghana and Mongolia

Source: cbonds.com, Mongolia 2018 Budget Proposal, Ghana Petroleum Fund Annual Report, 2016.

Risk 2. Revenue streams that are too small

Saving revenues in a fund can help countries mitigate serious macroeconomic challenges like the “Dutch disease” or excessive expenditure volatility. For instance, the Chilean government uses its Economic and Social Stabilization Fund to smooth year-to-year spending, guaranteeing a steady and predictable flow of money to ministries, so that each can plan the delivery of its public services years in advance.

However, a common myth is that the existence of oil, gas or mineral revenues requires a SWF. If resource revenues are small relative to the size of the economy or government revenue, some of the macroeconomic challenges that funds aim to solve are unlikely to emerge. Nevertheless, funds continue to be established where the flow of resource revenues is modest. The government of the Northwest Territories in Canada, for example, established a mineral royalty-financed Heritage Fund even though these royalties only account for approximately 3.5 percent of the territory’s fiscal revenues. Uganda and Zimbabwe have also established SWFs.

Risk 3. Uncertain resource revenue flows

Some governments do not even wait for oil or mineral revenue to start flowing before they establish an SWF. Cyprus, Mauritania, and Sao Tome and Principe, for example, established funds in 2013, 2006, and 2004, respectively. None has produced much oil or gas. The Kenyan government has prepared a draft law that would established an SWF, despite projections that oil revenues are unlikely to exceed 8 percent of fiscal revenues. The Lebanese authorities are also considering setting up a fund for oil and gas revenues.

Risk 4. Undermining the budget

Some SWFs invest both in foreign and domestic assets. However, as has been argued elsewhere, these funds have often undermined governmental oversight, and can be used as a source of corruption and patronage. More effective vehicles for domestic spending are the annual budget process and institutions designed for such purposes, such as national development banks or state-owned companies. Similarly, using a separate account within the budget—rather than through a new fund—can increase transparency and improve reporting requirements.

Still, officials in some countries are considering establishing funds in low-income settings with high economic growth potential. Afghanistan, Mozambique, Myanmar, Sierra Leone and Senegal are just some of the countries in the conceptual phase of SWF planning. Governments of countries that already have SWFs but also acute development needs and a pipeline of “shovel-ready” projects—such as Mexico and Nigeria—may wish to channel the money not through their funds but through the regular budget process.

Conclusion

There have been proposals to establish an SWF in nearly every country that has even a modest potential as a natural resource producer. However, authorities in countries with high debt payments, small or uncertain resource revenues relative to their economies, and acute development needs may wish to think twice before creating a “premature fund”.

In almost none of these cases do we believe that illicit activities are a major motivating factor. While some funds are used for corrupt purposes, our experience is that most are designed to demonstrate the government’s commitment to fiscal responsibility and good governance. Yet establishing an SWF in a low-capacity or poor governance environment will not necessarily improve the management of the country’s natural resource wealth, or achieve better fiscal outcomes. A more important priority for countries with a small pool of natural resources might be to ensure that the budget is well managed, and that government resources are spent to improve development outcomes. Establishing an SWF can distract the government’s attention from these more important objectives.

1Andrew Bauer is a public finance consultant. David Mihalyi is an economic analyst with the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). This article is adapted from a policy brief published on the NRGI webpage.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.