Posted by Gerhard Steger[1]

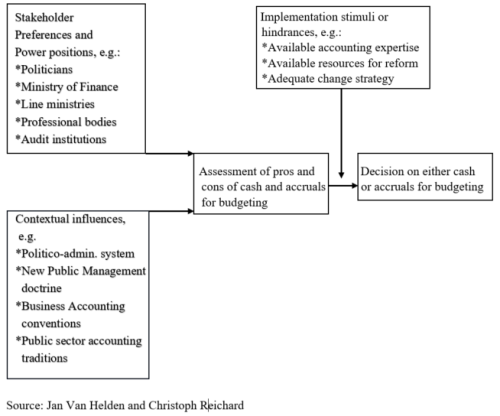

Accrual accounting and budgeting, which includes setting up a balance sheet, provides the most comprehensive picture of public wealth. It brings together all the accumulated assets and liabilities that the government controls and thus offers a broader fiscal picture beyond debt and deficits.[2] It is important to understand why governments in some countries have moved to accrual budgeting, while others stick to solely conducting budgeting on a cash basis, even if both groups of countries share an accruals-based financial reporting system. A recent study compares two countries that have opted to establish financial reporting on an accrual basis but keep cash budgeting (Belgium and Portugal) and two others (United Kingdom, Austria) that have adopted accrual budgeting.[3] The chart below outlines the framework used.

Decision-making Processes on Cash versus Accruals Budgeting in Government

The two groups of countries differed due to the attitude of the Ministry of Finance (MoF). In Belgium and Portugal the MoF was quite cautious and not fully convinced of the move towards accruals while in the UK and Austria the MoF was more strongly in favor. In the first two countries, the views of senior officials in the MoF perceived or anticipated that the attitudes of elected politicians would be opposed to accrual budgeting and that cash budgeting was required to ensure strict spending control. In contrast, in the UK and Austria, politicians and other stakeholders favored accrual budgeting because it aligned budgeting and reporting, provided a more comprehensive approach for allocating resources (hence the term “resource budgeting” in the UK), while allowing the government to retain full control of its cash requirements.

The implementation of accrual budgeting in Austria and the UK, and only accrual financial reporting in the two other countries was influenced by several factors. A lack of accountants and financial managers with requisite skills was a hindrance in all cases, although less so in the UK (easier access to private sector professionals because of less strict boundaries between the private and public sector). The whole implementation process was more stretched in Belgium and Portugal (between 10 and 25 years), while the UK (7 years) and particularly Austria (5 years for the first stage) managed the reform in a swifter manner.

The countries reviewed also managed the change process differently. In the UK and Austria, implementation was based on a well-developed and situation-specific change strategy. In the UK, for example, the National Audit Office and professional accounting associations were mobilized to provide specific support.

The administrative traditions and cultural patterns in the four countries had considerable impact on the reform process. In the UK, for example, the introduction of accrual/resource budgeting was part of a wider set of reforms in public administration that included the restructuring and downsizing of the civil service, and a substantial devolution of operational public financial management (PFM) responsibilities from the center to spending ministries and independent agencies such as the Debt Management Office.

The other three countries had a somewhat different point of departure, especially Belgium and Portugal which share the Napoleonic tradition of public administration. In these countries, the budget is perceived as an instrument for the legislature to decide on (cash) spending, and the inclusion of additional non-cash items in the budget thus met with strong resistance.

In the Continental-European setting, the Austrian case is somewhat exceptional. Although having a similar administrative legacy as Belgium or Portugal, the Austrian government undertook a far-reaching and uncompromising reform in quite a short period, supported by a successful change management strategy: The MoF drafted an amendment to the Austrian constitution which required the introduction of accrual budgeting. The amendment was unanimously approved by the parliament in 2007, but its implementation was delayed until 2013, during which time detailed legal provisions were drafted and capacity building and training activities were carried out. At the same time, the amendment to the constitution was regarded by all stakeholders as a fait accompli.

In all four country studies, members of the legislature were not closely involved in decisions on moving to accrual budgeting. In Belgium and Portugal, senior officials in the MoF anticipated the resistance of legislators to accrual budgeting, but nevertheless these same officials essentially made all the key decisions.

The study highlights the following factors that facilitate the successful implementation of accrual budgeting: (i) a reform-motivated government with strong leadership from the MoF; (ii) a dedicated task force within the MoF which guides the reform process; (iii) a government that is open to other advanced PFM reforms which assist the introduction of accrual budgeting; and (iv) support from an influential PFM community of professional bodies, academics, and accountancy firms.

[1] Consultant in public financial management; previously Budget Director in the Ministry of Finance, Director General in the Supreme Audit Institution, Austria and chair of the OECD Senior Budget Officials Network.

[2] IMF, Managing Public Wealth, 2018, p viii.

[3] van Helden, Jan and Christoph Reichard (2018), “Cash or Accruals for Budgeting? Why Some Governments in Europe Changed their Budgeting Mode and Others Not”, OECD Journal on Budgeting, Vol. 18/1.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.