Posted by Vincent Tang, Richard Hughes, Graham Prentice, and Mario Pisani [1]

In the UK, as in most other countries, fiscal policy-making has focused predominantly on the government’s financial flows (revenue, expenditure, borrowing). However, the IMF’s October 2018 Fiscal Monitor on Managing Public Wealth showed that the UK also has extensive holdings of other liabilities and assets. These more than trebled in the wake of the 2008 crisis, as a result the government’s financial sector interventions, unconventional monetary policy, and large operating deficits. It left the UK with net liability position of 125% of GDP in 2016, the second lowest net worth of the 31 countries sampled.

Whole of Government Accounts: What gets measured gets managed (eventually)

These facts are not unknown to keen-eyed accountants in Britain. In fact, the UK has been a pioneer in balance sheet reporting in the public sector, having produced the annual Whole of Government Accounts (WGA), which consolidates all the assets and liabilities of over 8,000 public sector entities into a single balance sheet, for over a decade. However, for much of this time, there has been limited use of the WGA in fiscal policy making. For example, the UK’s fiscal rules have long focused on borrowing and debt with the only asset recognized being liquid financial assets such as gold and foreign currency reserves.

However, 2017 saw an important departure with the launch of the government’s Balance Sheet Review (BSR) - the first time the government sought to take a hard look at the value it was getting from its extensive holdings of assets and liabilities. Part of the impetus for the review came from the government’s financial overseers and watchdogs. Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee and the National Audit Office had complained for years that the WGA had received insufficient attention. The UK’s independent fiscal council (the Office for Budget Responsibility) detailed the risks from the government’s extensive balance sheet in its first ever Fiscal Risks Report published in July 2017. The accounting profession itself played an important role in pressing for action, with the Association of Certified Chartered Accountants (ACCA), the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW), and the Chartered Institute for Public Finance Accountants (CIPFA) all issuing calls for the government to take its balance sheet more seriously.

Reviewing the balance sheet: Taking stock of the stocks

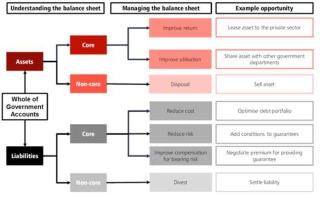

Engaging with scores of ministries and agencies entities over nearly two years, the BSR takes the WGA as its information base and applies an analytical framework to assess whether public sector entities are getting the best value from their assets and liabilities (Figure 1). The starting point is a segmentation of those holdings into those considered essential (or ‘core’) to the delivery of public services vs. those seen as non-essential (‘non-core’). Opportunities are then explored for increasing the return on or utilization of core assets, reducing the cost and risk of core liabilities, and divesting or disposing of non-core assets and liabilities.

Figure 1. The UK’s framework for assessing opportunities to improve balance sheet management (Click on the figure for a better image resolution)

Some low-hanging fruit already harvested

Due to conclude in autumn 2019, the BSR has already uncovered a number of major cross-government opportunities (and risks), summarized in an interim report in the 2018 Budget. They include:

- Getting smarter about intellectual property: The UK government is estimated to hold more than $190 billion (9 percent of GDP) in intellectual property and other knowledge assets such as patents, software, and data. Work is underway to improve the management of these assets and maximize the value they deliver to government and the wider economy.

- Retiring public-private partnerships (PPPs): The hidden cost of PPPs in the form of financing costs, inflexibility and fiscal risks was also highlighted by the BSR. As a result, the government announced it would no longer use this form of procurement for new projects.

- Disclosing the net impact of assets sales: The BSR has also prompted greater transparency regarding the balance sheet impact of government assets sales. The resale of assets acquired by the government during the financial crisis has raised around $120bn, but also given rise to call for more a more rigorous assessment of the value for money of these divestitures. New Asset Sales Disclosure Guidance requires the government to set out the proceeds of those sales relative to their holding value on the balance sheet and report any net gain or loss to Parliament at the time of sale.

- Getting a grip on contingent liabilities: In light of the growing size and variety of government guarantee programs, the Treasury introduced stricter controls and centralized monitoring of the issuance of new guarantees and other contingent liabilities and is looking at options for charging more market-based fees.

- Managing inflation-exposure: Having accumulated one of the largest stocks of inflation-linked debt among advanced economies, accounting for around one-quarter of the total government debt stock, the government is steadily reducing issuance of inflation-linked gilts.

- Digitizing government property: The government is launching a geo-spatial Digital National Asset Register to better manage and commercialize its $550 billion of property assets.

Challenges ahead

Having identified these system-wide reforms, the next challenge is for ministries to improve the financial, economic, and social returns on their assets and liabilities, which will inform the setting of multi-year financial settlements for each government department in the autumn Spending Review.

Once the BSR has concluded, the remaining challenge will be to embed balance sheet perspectives into government financial management, accountability and the wider public debate. Progress has already been made. The government published its response to the biennial Fiscal Risks Report including a dedicated balance sheet chapter, and Parliamentary hearings and National Audit Office sessions have focused on reforms to the student loans system, contingent liabilities, and the Bank of England’s balance sheet. A leading economic think tank, the Institute for Fiscal Studies regularly publishes reports on the UK balance sheet. Even Britain’s highest circulation tabloid newspaper, The Sun, reported on Britain’s ‘hidden debt mountain’ revealed by the Fiscal Monitor.

However, there remains considerable scope to inform and encourage public scrutiny and discussion of these topics. We hope the BSR represents an important step in bringing the balance sheet into the heart of the public debate about Britain’s fiscal future.

[1] Vincent Tang is a Technical Assistance Advisor, Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF, formerly a staff of HM Treasury, UK. Richard Hughes is former Fiscal Director of HM Treasury between 2016 and 2019, and formerly Division Chief in the Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF. Graham Prentice is Head of Balance Sheet Analysis in HM Treasury. Mario Pisani is Deputy Director of Debt and Reserves Management in HM Treasury.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.