Posted by Teresa Curristine, Alberto Soler, Virginia Alonso-Albarran, Gemma Preston, Nino Tchelishvili, and Sureni Weerathunga[1]

The COVID-19 crisis has disproportionately impacted women and increased the urgency of developing and implementing policies to address gender inequality. Gender budgeting (GB) is one of the instruments governments use to help tackle gender inequalities. Recognizing that a government’s policies and funding decisions impact men and women differently, GB applies a gender lens or perspective to identify gaps in fiscal policies and the budget process and provides the tools to address these gaps. G20-Women, the official G20 engagement group on gender equality, has called for greater investment in GB to ensure that fiscal policies advance gender equality in the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and in the longer term.

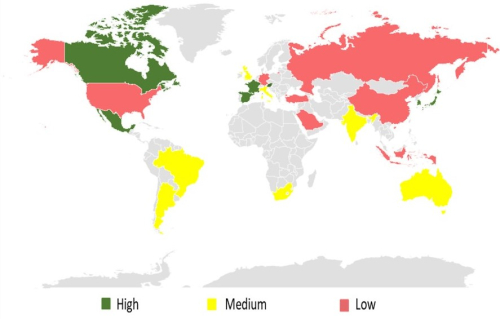

A recently published IMF paper takes stock of gender budgeting practices in G20 countries. It benchmarks country performance using a GB index and data gathered from an IMF survey. All G20 countries have enacted gender focused fiscal policies but the budgeting and planning tools to operationalize these policies are generally less developed. There is significant variation in GB practices across countries (see Figure 1), but the average performance across the G20 countries is relatively low. No country is rated as achieving overall advanced practice.

Figure 1. G20 Gender Budgeting Index (GBI): Performance by Country (High, Medium, Low)

Source: IMF Survey and IMF Staff. Note the GB index is focused on federal government and does not capture GB policies at the subnational government level.

Across the budget cycle, the study identifies clear strengths and weaknesses in GB practices. GB institutional frameworks and budget preparation processes are generally stronger than budget execution and auditing practices – but opportunities for improvement exist in all areas. GB features of public financial management (PFM), where they are in place, tend to operate more as an ‘add-on’ to the standard PFM framework, rather than as an integral part of the budget and resource allocation process.

All countries can do more to integrate a gender perspective throughout the budget cycle to get the biggest ‘bang-for-their-buck’ in terms of their GB reform efforts. For example, including gender in the budget circular but not incorporating GB tools in the budget execution and reporting phases, may allow countries to better fund gender programs. But it does not provide any information on how a program’s money is spent, whether gender objectives are achieved, or how the design of spending programs could be improved.

The IMF study shows that powerful GB tools are being underutilized and countries are missing out on valuable opportunities to drive policy change and fight gender inequality. Too few countries assess the upfront impact of policies on gender and/or evaluate ex-post the effectiveness of policies and programs. Such analysis can help raise awareness of gender gaps and illuminate a dialogue on how policies and programs influence gender equality. However, the analysis needs to be integrated into budget decision making if it is to result in better targeted policy. Further efforts to improve GB budget execution practices, and ex-post evaluations are necessary, including by enhancing program and performance-based budgeting efforts. The study emphasizes that PFM fundamentals should be reinforced to support GB implementation and initiatives to strengthen GB synchronized with PFM reforms to catalyze progress.

Strong political backing for improving gender outcomes, a finance ministry that is firmly in the ‘driver’s seat’, and a well-tuned legal framework are key to successful GB reforms. The variable fortunes of GB highlight the importance of promoting wide societal and political support for the required institutions and practices if the reforms are to endure changes in governments. Empowering the finance ministry to develop common methodological guidelines, include gender considerations in budget circulars, and publishing progress reports with the budget, should help improve GB analysis and overcome major implementation challenges.

Globally, support for GB is broadening and there are considerable opportunities for countries to improve their current practices - regardless of their level of development or income. Strong performance in GB implementation does not appear to be heavily dependent on a country’s level of development. Among the G20, there are some advanced countries that perform poorly and, among non-G20 countries, some low-income countries’ GB practices match those of emerging markets and advanced countries in some areas.

Effectively responding to the COVID-19 pandemic means transitioning to GB practices that are more influential in shaping and changing policy decisions. The crisis has highlighted how the failure to consider gender aspects in the design and implementation of policies can have an unintended economic impact. It is important that GB PFM tools help disentangle the gender impact of policies during the design and budgeting phases, better track expenditure effectiveness and improve accountability. Making the impact of policies on equality more visible through better analysis and reporting will help to promote implementation and improve results. The pandemic presents new challenges for the implementation of GB, while underscoring the urgency and importance of making progress in this area.

[1] Teresa Curristine is a Deputy Division Chief, Alberto Soler and Virginia Alonso-Albarran are Senior Economists, Gemma Preston and Nino Tchelishvili are Technical Assistance Advisors and Sureni Weerathunga is a Research Assistant in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.