Posted by Greg Rosenberg[1]

This blog is based on a presentation delivered to the Public Expenditure Management Peer Assisted Learning (PEMPAL) group of countries in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia in October 2021.

National budget documents provide an excellent platform for governments to communicate fiscal policy, outline choices and trade-offs, and promote accountability in public finances.

Transparency is the sine qua non of budget reporting. The very first line of the IMF’s Fiscal Transparency Code explains that fiscal reports should provide a comprehensive, relevant, timely, and reliable overview of the government’s financial position and performance. Budget documents need to be clear, credible, comparable, analytical, and relevant. But all too often, they fall short of one or more of these measures.

For many governments the problem originates in a compliance driven process that leads to the publication of enormous volumes of information. Such documents rarely provide useful analysis or a narrative thread that can help policy makers, investors, or the public obtain a clear picture of the health and direction of the public finances. And the answer to the question posed in the image above – are you communicating? – is generally “No” – or at least, not very well.

While this approach can be said to be comprehensive, because “it’s all there”, extremely lengthy and dense budget documents generally fail to support effective public policy, decision-making, and the democratic process, because so few readers can possibly wade through all the information provided. From the standpoint of communicating clear macro-fiscal objectives, this approach is a non-starter.

This brings me to the concept of transparency, which is often narrowly defined in public financial management discourse. Yes, finance ministries should publish all the relevant information, from economic and fiscal outcomes and forecasts, to comprehensive fiscal risk assessments. Detailed spending information must also be available to the public, with data sets accessible to researchers and journalists. But these foundational elements of transparency are only the starting point. Transparency is the quality that makes it possible to see through something – or that makes a document easy to understand. The act of publishing information does not equate to transparency.

The October 2021 Fiscal Monitor notes that strong budget institutions, alongside clear communication and fiscal transparency, enhance credibility. Credibility, in turn, improves access to credit and secures more room for maneuver in times of crisis.

How then can finance ministries use the budget documentation process to strengthen transparency, clear communication, and credibility? The 10 principles outlined below are a useful starting point. I will address a few of them here.

Who is the budget document written for? Invariably, there are multiple target audiences – from government officials to economists, legislators, regulators, and the financial markets. Ultimately, however, the documents should be written in a way that is accessible to the public. This means conveying economic and fiscal concepts in a way that is clear to the non-specialist. This approach requires a complete change of mindset in many finance ministries.

Clear and concise budget documents support effective fiscal policy. Unfocused, overlong documents do not. Clear writing means avoiding jargon and explaining technical concepts; preferring concreteness to abstraction; analyzing data (not merely reporting it); and writing to the point rather than in a circular manner. Of course, in dealing with complex technical concepts, these things are often easier said than done.

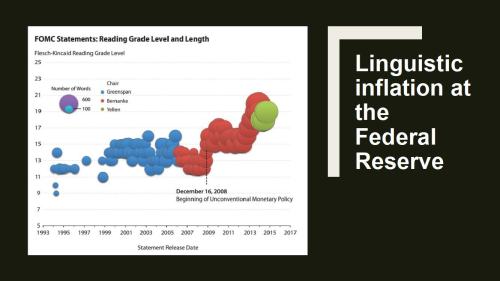

For example, consider the evolution of statements produced by the U.S. Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) following the 2008 financial crisis. A 2014 study by the St. Louis Fed shows a significant increase in the length and complexity of FOMC statements, coinciding with the increasingly complex operations that we now know as quantitative easing. The figure below shows the reading grade level (bubble height) and the length (bubble size) of FOMC statements between 1994 and 2014. In the early 1990s, the statements ranged from about 50 to 200 words, and were accessible to individuals with an education ranging from the first year of high school to two years beyond high school. By 2014, statements averaged 800 words and readers required an education level three years beyond a four-year college degree to understand them – somewhere on the plane of Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil.

Addressing this balance will always be a challenge to be tackled, rather than a problem to be averted.

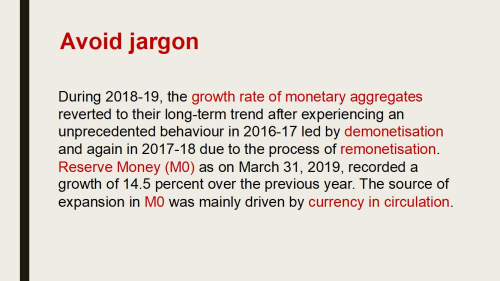

Clear budget documents should avoid jargon. The slide below illustrates the kind of language that often appears in a budget document. Beyond economists who focus on monetary policy, the terms in red are largely incomprehensible.

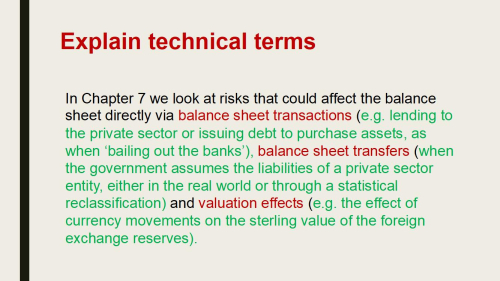

Technical terms need to be explained. Below is one approach, taken from a report published by the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility. The terms highlighted in red are explained in green (my emphases).

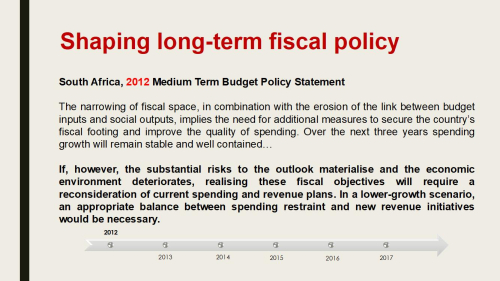

Finally, good budget documents tell a story. This is not about creating works of fiction (though some may think so). A story is a narrative manner of describing developments. The budget narrative should convey the policy framework, the key messages, and the data in a way that ties it all together. This approach lends itself to flagging risks, highlighting choices, hinting at future policy considerations, and promoting public debate and accountability, as shown below in an excerpt from South Africa’s 2012 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement.

Where budget documents as used as effective and credible tools to communicate and strengthen public policy and accountability, there is generally high-level political support for this approach. That’s because producing clear, accessible, effective reports that do not shy away from discussing difficult problems and presenting tough choices is rarely the easy political choice. But over the long term, it pays off in improved public finances.

[1] The author is Managing Director of Clarity Global Strategic Communications (Washington, DC, and Cape Town, South Africa), and advises governments around the world on clear budget and fiscal communications.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.