iStock.com/Taveesaksri

Posted [1] by Sailendra Pattanayak, Racheeda Boukezia, Yasemin Hurcan and Ramon Hurtado[2]

Governments in most fragile states (FS) and several low-income developing countries (LIDCs) face cash management challenges due to their relatively low administrative and institutional capacities. Available public funds in these countries are often dispersed outside the control of the ministry of finance or treasury. This hinders a clear view of the overall cash balance and potentially weakens budgetary and financial controls, leading to leakages of cash. In the absence of reliable cash forecasting, these countries typically resort to cash rationing to meet their priority spending needs, often in an ad hoc manner, which can adversely affect budget execution and the achievement of fiscal policy targets.

These cash management challenges are further compounded by broader fiscal management issues in many FS and LIDCs and their limited fiscal space. The revenue bases of these countries tend to be smaller, less diversified, and consequently more volatile. Also, a large part of their total spending envelope is nondiscretionary, leading to cash shortages when cash inflows are lower than projected. The countries also lack access to financial markets or have shallow financial markets from which to borrow. Most of them rely on donor money to finance a large portion of their budgets, but the disbursement of donor funds is often unpredictable. These issues, often coupled with unrealistic budgets, lead to the build-up of arrears, and may have ripple effects on private consumption and the countries’ financial stability.

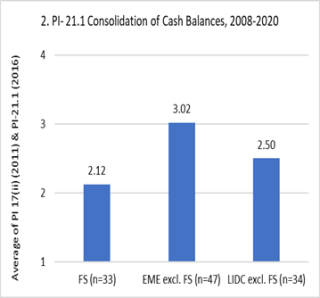

The overarching goal of government cash management is to ensure the availability of cash to pay for expenditures when they are due while minimizing the cost of funds. Achieving this goal allows the smooth execution of the government budget and the achievement of fiscal policy targets. The annual budget provides estimates of countries’ revenue, expenditure, and financing needs for the entire year. But the actual day-to-day flows of government receipts and payments are typically not smooth because of seasonal mismatches of tax and nontax receipts, grant and loan disbursements, and government expenditures. A sound cash management function helps address mismatches between cash needs and cash availability in the most cost-effective way thus maximizing liquidity and minimizing the cost of funds. However, the development of a good cash management function is among the most challenging PFM reforms in FS (see Figure 1 below).

Cash Management Function in Fragile States Relative to Other Country Groups

Source: Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) database (www.PEFA.org).

Note: EME = emerging market economies; FS = fragile states; LIDC = low-income developing country.

A new IMF How-to Note sets out the key objectives and core building blocks of a good cash management function in FS and LIDCs. The paper offers practical approaches, provides many examples of country practices, and proposes several measures to build cash management capacity in a progressive manner. It is important to develop a reform strategy with specific measures that take account of the countries’ absorptive capacity and potential political economy-related constraints. The reform strategy should cover three interrelated areas: (i) consolidating cash resources under treasury oversight through a treasury single account (TSA) system; (ii) forecasting short-term cash inflows and outflows; and (iii) managing cash balances and ensuring institutional coordination for sound decision making. Reforms in these areas do not need to start at the same time. They can proceed in parallel, but as the reform progresses, the interlinkages among these three areas should be explicitly identified and addressed to keep the reform strategy on track and derive the full benefits.

[1] This How-to Note is complemented by two other upcoming capacity development products: (i) Cash Forecasting and Analysis Tool (CFAT) and its associated user guide (Williams, Hurcan, Nguenang, Pattanayak, Ryan, and Gallardo 2022); and (ii) Questionnaire-Based Diagnostic Tool to understand the starting point, constraints, and reform opportunities that inform the cash management reform strategy (Boukezia, Gros, and Pattanayak 2021).

[2] All Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.