In our recent research at ODI’s Digital Public Finance Hub, we are critical of the prevailing paradigm for how we think about digital transformation within public financial management (PFM). This paradigm is characterized by a solution-driven approach, a closed and siloed technology architecture, and an unsuitable and outdated funding and delivery model. In short, we feel it fails to live up to the promise of a digital revolution in public finance and is not keeping pace with wider developments in digital government.

For PFM to be digital, three big shifts in mindset are needed: a shift in how we approach PFM reform, a shift in how we think about the technology architecture for PFM, and a shift in how we fund digital transformation.

Why are we critical of the prevailing paradigm?

Our paper points to three problems:

1. PFM is rigid and losing its policy relevance

Over the last two decades the PFM community has become increasingly confused between PFM’s role as a means to an end, and PFM reforms as ends in and of themselves, prioritizing form over function.

This has happened for very understandable reasons. Successful reforms in a small number of countries became ‘best practices’, which in turn fed a proliferation of diagnostic tools and conventions for other countries to comply with and pursue as part of their PFM reform agendas. As a result, we have seen a plethora of IT-driven planning, budgeting, procurement, accounting, auditing, and other reforms that are often unmoored from the policies a government is trying to deliver and the problems they are trying to solve.

2. A closed and siloed technology architecture

IT solutions for different PFM functions are often siloed from each other, as well as from other government IT systems.

While governments have become much better at producing financial information, they are still not very good at understanding whether their fiscal policies are having their intended impact. A big reason for this is that IT solutions are siloed in different government functions and departments, often using unharmonized data structures. For example, inconsistencies between the chart of accounts for budgeting and accounting make it difficult to understand if spending is in line with plans. And, siloed sector management information systems make it arduous (and in some cases impossible) to bring together data on inputs, outputs, and outcomes in ways that are useful for policy-making.

3. An unsuitable and outdated funding and delivery model

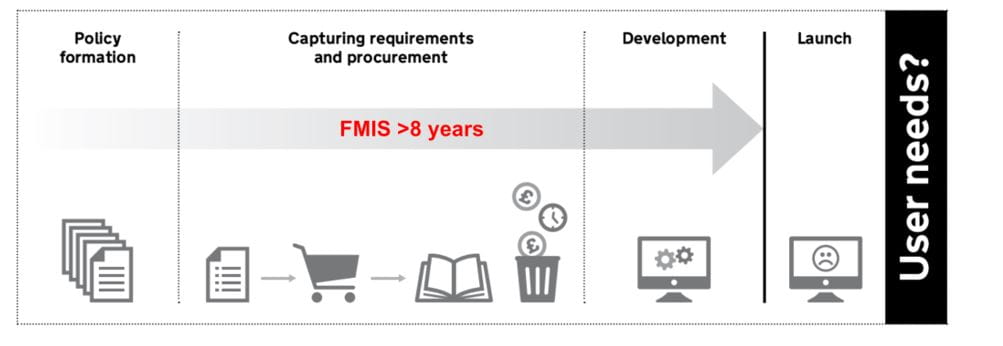

The way governments fund digital transformation incentivizes a solution-driven approach to PFM reform.

Too often governments try to deliver digital infrastructure in the same way they deliver physical infrastructure. They attempt to specify all their requirements up front in a business case, contract suppliers to deliver the IT system, and budget only for the up-front capital cost. This process can take so long (an average of 8 years for a financial management information system) that the requirements have changed by the time the system is eventually implemented. More often, the project encounters internal resistance, because those specifying the requirements have not consulted well enough with the actual users of the system.

What needs to change to bring public finance into the digital era?

For all these reasons, we recommend three big shifts in thinking.

In isolation none of these are new recommendations, but together they constitute an emerging paradigm – digital PFM. A finance ministry adopting these shifts in mindset could generate important spillovers for the kind of whole of government approach to digital transformation towards which many governments now aspire.

1. A funding and delivery model for sustainability

Funding and delivering digital infrastructure are different from funding and delivering physical infrastructure.

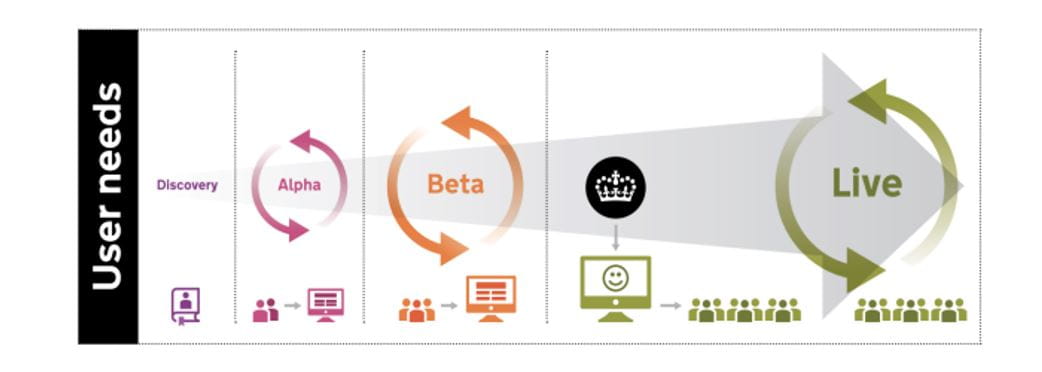

Modern approaches to developing and deploying software emphasize: (i) starting with user needs; (ii) scaling up incrementally based on user testing; and (iii) continuous iterative improvement even after the system goes live. This implies a shift in thinking, from capital budgets for IT projects, to recurrent budgets for in-house digital skills like user research, product management, and agile procurement.

Figure 2: Agile Delivery according to the UK Government Digital Service (Source)

2. The PFM system as part of a wider ecosystem of data, platforms, and services

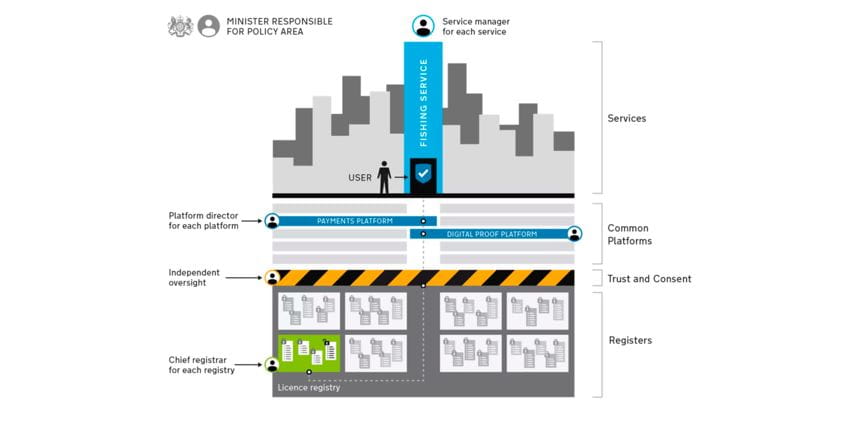

The capability to effectively exchange data and information across and between layers of government – often referred to as interoperability – requires a silo-busting mentality.

New models for thinking about the role of government in the digital era emphasize a reorganization of government around data, platforms, and services. This means shifting to a much more open architecture based on standardized open application programming interfaces (APIs).

Figure 3: Making ‘government-as-a-platform’ real (Source)

More generally, PFM professionals must start thinking about (and testing) interoperability ex-ante rather than lamenting its absence ex-post. That may ultimately mean abandoning pre-conceived notions of what constitutes an integrated financial management information system (IFMIS), and recognition that such things need to continuously evolve in line with user needs.

3. A flexible and responsive PFM system

Like the IT systems that underpin them, PFM processes require ongoing iterative redesign to provide a system that is flexible to the ever-evolving needs of users and responsive to the problems policy makers are trying to solve.

The pandemic tested PFM systems. Some governments were able to leverage their digital capabilities to respond to the crisis in certain areas. The UK furlough scheme and Togo’s Novizzi cash transfer scheme stand out among examples. In other cases so called best practices were abandoned for the sake of expediency and at the cost of transparency and accountability.

Capabilities to solve problems will be necessary to deliver on policy promises like universal health coverage and respond to emerging crises around climate change and inequality. This means recognizing PFM and digital transformation as means to an end and bringing them together in a problem-driven approach to PFM reform.

The role of finance ministries in digital transformation

As controllers and coordinators of the public finance system, finance ministries can either drive digital transformation or hold it back.

First, finance ministries need to recognize that they are providers of digital services to the rest of the civil service – whether this is a tool to prepare a budget or claim expenses. It is in their interest that these users are well served by technologies that meet their needs, and work well with other technologies they use to do their jobs. Too often finance ministries focus on their own needs.

Second, finance ministries control how much funding is available, and how it is made available. They can support a shift towards more agile and iterative approaches to funding and delivering digital services, and the in-house digital capabilities required to manage them. Again this is in their interest as it can deliver better value for money.

Third, and more importantly, digital transformation is about much more than just technology – it also encompasses people, processes, and culture. Finance ministries need to be part of a broader shift from a culture of compliance to one where institutions and individuals are rewarded for turning policy into delivery, and are held accountable for the outputs and outcomes delivered.

Where to start will vary by context. But starting with a problem, rather than a solution, is always a good approach. The designers of diagnostic tools should also keep this in mind.

A summary of the recent papers “Digital public financial management: An emerging paradigm” and “Making public finance digital: Challenges to the emerging digital public financial management paradigm” by ODI and Public Digital.