India's fiscal framework involves substantial transfers from the union government to sub-national agencies, like states and the urban local bodies (ULB), and further downstream to businesses and citizens. In the current fiscal year, the Government of India (GoI), plans to transfer USD 266 billion, or 7% of India’s GDP, to states through Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS). The public finance systems that undepin these fiscal transfers are key to India’s ability to spend and spend well.

In July 2023 the GoI rolled out SNA-SPARSH for “just-in-time” (JIT) release of funds allocated to the states under CSS. In theory, JIT would eliminate the time gap between the physical event, i.e., the work for which the payment is due, and the fiscal event, i.e. the outward flow of money from the treasury to the end beneficiary—a person (G2P), a business (G2B), or other government agency (G2G). Such a system will have two core attributes:

- Efficient fund release: “pulling” funds from the treasury and passing them on directly to the beneficiary’s bank account;

- Efficient payment processing: pulling funds in “real-time,” that is, just when payment for the work is due, based on rules triggered through algorithms.

An implicit assumption in fiscal transfers is that funds will be pushed downstream, but SNA-SPARSH turns this assumption on its head. It allows an agency that makes expenditures to pull funds up to the sanctioned limit when needed. Smart payments build upon SNA-SPARSH’s capabilities and pushes the envelope on JIT.

A brief history of (just in) time

For many years CSS funding operated through a cascading fund transfer mechanism, resulting in government bank accounts holding idle funds for extended periods before the implementing agency made the expenditure. All that changed after GoI introduced the Scheme Nodal Agency (SNA) system in July 2021 to consolidate banking arrangements, reduce float, and enhance transparency in fund utilization.

Integrated treasury systems significantly reduced the number of government accounts (from 1.8 million to 3,300) and the float, and provided real-time information onfund releases and expenditures (SNA dashboard). India’s Finance Minister projected an annual savings of USD 1.2 billion from the SNA reforms.

SPARSH—the “pull” to complete the fund release

Under the SNA, the funds are still being “pushed,” albeit with fewer intermediate halts, in shorter bursts, and with a good view of where they are at any given time. While the gap between the fiscal and physical events has reduced, it was not eliminated.

However, SNA-SPARSH marked a transition from a credit push (a-priori release of funds to various implementing agencies) to a debit pull-based fund transfer system in which a debit to the central pool is triggered only when implementing agencies issue payment instructions on the system. By design, SNA-SPARSH can “pull” funds in real time to the end beneficiary’s account, which takes it closer to JIT. These design features:

- Enable a seamless flow of information across three disparate systems - GoI’s PFMS, the financial management systems of a given state (IFMIS) and the RBI’s e-Kuber platform;

- Allow CSS, SNA, and implementing agencies to access the platform —the last two via IFMIS;

- Create CSS-wise sanction orders for each state at the start of each financial year.

Under SNA-SPARSH, the SNA or implementing agency generates the payment files that trigger the release of funds into the beneficiary’s bank account. However, there is a time lapse between the generation of payment files and the instance when the work meets the payment milestone. Thus, the holy grail of just-in-time payments is still distant, as funds are not pulled in 'real time’.

Cometh the hour, cometh the smart payments

The missing piece in the JIT puzzle is a payments processing system that can process payments, that is, generate payment orders algorithmically upon fulfillment of payment conditions for payees, such as vendors and citizens. Further, it should “talk” to the IFMIS system to permit “straight-through processing” of invoices without manual intervention. In other words, the system can generate the payment files that SNA or implementing agencies can feed into a state’s IFMIS.

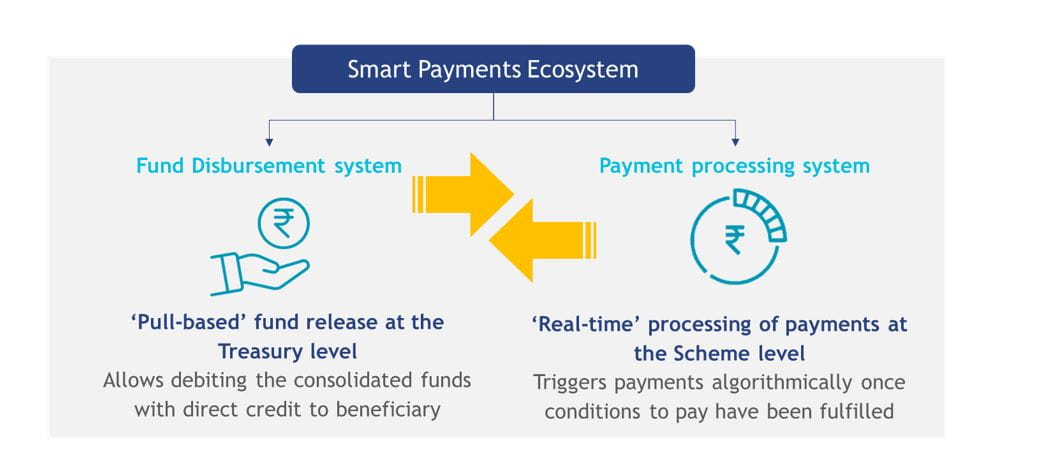

When integrated with a pull-based fund transfer system like SPARSH, such a “smart” payments system creates a “smart payments ecosystem” that meets both the conditions of pull-based fund disbursement and the real-time processing of payments. See the chart below.

One such smart payments ecosystem is currently being implemented by the state Government of Odisha for its MUKTA scheme. The scheme was launched to tackle job vulnerability in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. MUKTA faced challenges in the timely payment of wages to scheme beneficiaries (wage-seekers, SHGs, and material vendors), idle parking of project funds, and inefficient project management. MSC designed the “smart payments ecosystem” that coupled a Virtual TSA-based JIT funding system for the state’s Finance Department and a payment processing system “MUKTASoft,” for the Housing & Urban Development Department.

The solution allows the ULBs to pull funds from the state’s consolidated fund directly into the end beneficiary’s bank account in real time upon completion of payment milestones. It also incorporates autonomous rule-based processing of payments that has streamlined the process and reduced the administrative burden on ULB officials executing the project on the ground. The pilot is underway in 23 of Odisha’s 149 ULBs, and early results indicate the elimination of float and a reduction in payment delays by 57% to the beneficiaries. MSC estimates that the smart payments system can save the exchequer of a state like Odisha (GDP of USD 100 bn) about USD 50 million annually.

The journey toward an effective and efficient fiscal transfers in India has taken a leap forward with the SNA-SPARSH model. While challenges persist, ongoing experiments and successful pilots like MUKTA can transform public finance by making fiscal transfer just-in-time and pave the way for more effective and accountable governance.