Posted by Richard Allen and Gerardo Uña[1]

Financial management information systems (FMISs) are a vital tool for governments to process, store, and report on financial information and transactions. A well-functioning FMIS provides timely, reliable, and comprehensive reports that support the government’s fiscal policies and fiscal rules, and the formulation, control, monitoring, and execution of the budget. If used well, these systems promote financial integrity and transparency.

Huge amounts of money have been poured into FMIS platforms. The World Bank alone has invested more than US$4.9 billion in these systems since the mid-1980s. Yet, governments and donors alike have almost invariably underestimated the institutional challenges of implementing FMIS projects. The outcome of these investments in many cases have been poor. Projects have suffered from a misalignment of incentives, delays, underbudgeting and low level of efficiency and effectiveness. Long-term maintenance contracts negotiated by vendors are not always well matched to countries’ needs. More seriously, the design of FMISs has not kept pace with advances in technology and digitalization, or with the modernization of PFM-related business processes.

These issues are discussed in a new study[2] published by the IMF—“How to Design a Financial Management Information System: A Modular Approach”. At the core of the study is a survey of 46 developing countries and emerging countries. While some systems are working well, the survey identifies many failings of FMISs in these countries, including:

- Problems in the generation of reliable and timely fiscal reports;

- Failures to integrate a modern chart of accounts;

- Weaknesses in the management and control of the budget;

- Absence of a data warehouse that generates detailed accounting and budget information;

- Deficiencies of electronic payments and bank reconciliations;

- Insufficient support for government banking functions;

- Unreliable and untimely information for cash management;

- Incomplete coverage of budget entities in the FMIS; and

- Software, hardware and connectivity problems.

The reasons for these failings are many, including flaws in the design of the system, lack of ownership by the government, weak project management, and inadequate use of available technology.

A key question discussed in the paper is how to improve an FMIS by revamping its functionalities and adopting new technologies where appropriate rather than replacing the system with an entirely new one. Digitalization is no longer simply an option to reduce costs and enhance business processes. It also allows users to automate controls, reduce workload, improve transparency, and make the systems more secure from fraud and corruption.

Looking ahead 10 or 20 years, digitalization is likely to revolutionize the nature of FMISs. A fully integrated set of functions and processes may be replaced by virtual systems in which the finance ministry or state treasury collects financial data from a wide variety of sources and transforms those data into the required formats and reports, thus enhancing their oversight of public finances.

The study puts forward two key propositions. First, it argues that FMISs should focus on the “core” functions of public such as accounting and financial reporting, budget execution, and the treasury and cash management operations. Second, it argues that by employing modern technology—such as Applications Programming Interfaces (API) and web-based platforms—to improve connectivity between different parts of the system, replacing the FMIS with an entirely new system can be a poor strategy.

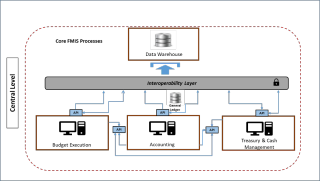

Figure 1. Schematic Representation of a Modular Approach

A better and more cost-efficient approach may be to update or replace one or two core modules of the system that present weaknesses— accounting or cash management perhaps—the so-called “modular approach”. Functionalities or modules that are working well should be maintained but be better linked so that an efficient sharing of fiscal information is ensured. The efficient exchange of data requires a common set of standards to be established for all relevant information fields (e.g., the budget classification and the organizational structure of government), and the consolidation of fiscal information in a data warehouse.

The paper notes that FMISs like many other information systems need to face up to emerging challenges related to digital innovations, such as machine learning, and the utilization of cloud computing. The systems are also highly vulnerable to cybersecurity threats, but countries do not always give these challenges appropriate attention.

The paper argues that successful design and implementation of an FMIS depends critically on strong leadership from the finance ministry and building a consensus across government on the design and operation of the new system. Such leadership and consensus are often lacking in developing countries which explains why some governments are still struggling to implement an effective system after decades of unsuccessful multi-million dollar investments.

FMISs also need to keep pace with planned PFM reforms. For example, modern public finance systems call for countries to expand the coverage of their fiscal planning and reporting, by bringing local authorities, extrabudgetary entities and public corporations into fiscal reports and the budget and broadening the coverage of the government’s balance sheet. Developing areas of PFM such as gender budgeting, fiscal risk management, anti-corruption strategies, and climate change may also need to be incorporated in the FMIS design. A serious risk is that governments simply aim to replicate existing business processes in the FMIS rather than using the latest technology to incorporate modern principles and practices of public finance.

[1] Senior Economists, Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF.

[2] The study was prepared by Gerardo Uña, Richard Allen, and Nicolas Botton.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.