Posted by Bruno Imbert, John Ralyea, and Ashni Singh[1]

The COVID-19 pandemic and economic fallout has created financial challenges for firms around the world, including many state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in Africa. A recently published IMF Note offers guidance on whether governments should provide temporary exceptional financial assistance and, if so, how. The Note discusses the circumstances under which support may be provided, key guiding principles on the measures that could be used, and the need for accompanying governance and oversight reforms. The Note’s focus is on African SOEs, but its principles and messages apply across other regions.

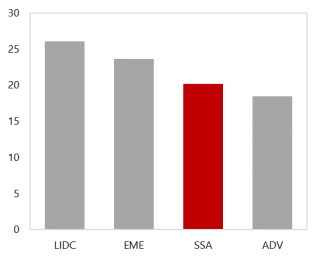

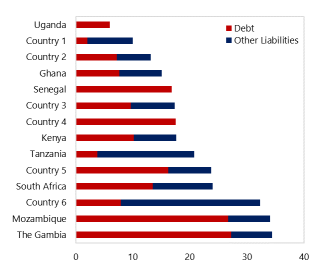

In many countries, SOEs play a systemic role in public finances and the economy. Across a subset of African countries, SOE liabilities average 20 percent of GDP (Figure 1).[2] SOEs also contribute significantly to government revenue in some countries and are often concentrated in essential and strategic sectors. They provide basic services such as electricity (generation, transmission, and distribution), water, telecommunications, and other public utilities. SOEs are also often a key player in strategic sectors (e.g., natural resources, strategic infrastructure, agriculture, etc.). Some SOE failures could result in systemic problems for the economy and affect efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19 especially if the provision of basic services is threatened.

Source: IMF staff estimates.

Many SOEs were in financial distress before COVID-19. The crisis has further elevated concerns about their liquidity position, and, in some cases, their solvency. Governments will face trade-offs and other considerations in deciding whether and when to support SOEs and how to deliver this support. Key issues include: (i) prioritizing between many demands using a cost-benefit analysis approach; (ii) targeting support to the most systemically important SOEs whose failure could endanger the provision of basic services; (iii) treating SOEs and private competitors equally in relation to government support; and (iv) ensuring full transparency.

Governments also need to assess the strengths and weaknesses of various measures that may be available to support SOEs. This assessment should consider the financial health of the SOE, the capacity to deliver a timely response, and implications for the government budget. Options include:

- Strengthening SOE cash flow: Examples include tax and social security contribution deferrals to mitigate liquidity pressures, and subsidies to compensate for policy mandates. These measures would have an immediate impact on the government budget.

- Strengthening the SOE balance sheet: This could be achieved through equity injections that provide cash to the SOE but could be prohibitive for cash-strapped governments. An alternative would be debt-for-equity swaps that strengthen the SOE’s financial position and limit the cash outlay of the government but provide little fresh liquidity to the SOE.

- Facilitating SOE borrowing: This can be done through government guarantees for SOE borrowing or on-lending to SOEs. These have limited or no immediate impact on the government budget but could imply significant fiscal risks. Loans from public banks are another possibility.

- Bringing in private investors. Strategic investors would inject capital and provide management and operational expertise, but this needs to be done carefully to avoid fire sales during market nadirs.

The question of whether, how, and to what extent support should be provided to SOEs also involves transparency and governance considerations. In the short run, there should be full transparency on all support and conditions attached. Any support provided to SOEs should be approved by parliament and reported in budget documents (including below-the-line operations, use of extrabudgetary funds, or contingent liabilities).

There also needs to be a commitment to medium- and longer-term reforms including:

- Effective SOE oversight and a strong ownership function. There need to be clearly demarcated roles for the ministry of finance, sectoral ministries and, where they exist, the SOE oversight body, and a comprehensive annual report on the SOE sector as a whole.

- SOE financial transparency and accountability. Individual SOEs should publish audited financial statements in a timely manner. In addition, SOE balance sheets should be reviewed and major assets revalued periodically.

- Corporate governance. Minimum corporate governance standards need to be in place to ensure that the responsibilities of boards of directors are clear, that arrangements for measuring, monitoring, and assessing SOE performance exist, and that such information is publicly disclosed.

- Strengthening fiscal risk management. Countries should progressively strengthen their identification, management, and disclosure of fiscal risks.

- Updating legal frameworks. The SOE sector needs a modern legal framework to govern its operations. In many African countries, such a legal framework is either not in place or is outdated.

The IMF has developed a number of tools to help countries strengthen SOE oversight and fiscal risk management and improve the finances of their SOE sector. These tools include conducting assessments that measure the size of the SOE sector and its impact on public sector finances (e.g., compilation of the Public Sector Balance Sheet, conducting a Fiscal Transparency Evaluation or an SOE Health Check) or providing capacity development to help countries enhance SOE monitoring and risk mitigation.

SOEs may experience similar pandemic-induced financial difficulties as private firms. The Ethiopian Prime Minister and 2019 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Abiy Ahmed has recently drawn attention to the crisis facing state-owned African airlines. Temporary and exceptional relief can help SOEs that have a strategic or systemic importance, and their customers, weather the pandemic storm.

This article is part of a series related to the Coronavirus Crisis. All of our articles covering the topic can be found on our PFM Blog Coronavirus Articles page.

[1] Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF.

[2] Average for the 14 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa for which data is available in the IMF’s PSBS Database, Fiscal Transparency Evaluations (FTEs), and Capacity Development (CD) reports. Data exclude central banks and are largely non-financial corporations. For these countries, on average, SOEs account for 21 percent of public sector liabilities and 34 percent of assets.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.