Posted by Vivek Ramkumar and Claire Schouten[1]

So many lives have been upended by the overwhelming health and economic impacts of COVID-19. The good news is that governments have made major spending commitments to shore up their battered economies and to provide direct relief to their populations. The IMF estimates that countries have already announced nearly $12 trillion in emergency spending measures.

However, these measures followed expedited processes and did not receive the same level of scrutiny as annual national budgets. A key challenge that countries are now confronting is to ensure that emergency funds contribute to the recovery and reach their intended beneficiaries.

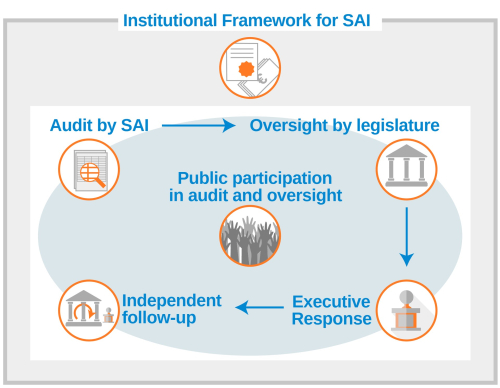

Supreme audit institutions (SAIs) have a lead role in providing such oversight. But new research from the International Budget Partnership (IBP) and the INTOSAI Development Initiative (IDI) shows that for SAIs to deliver results, they must be supported by an “ecosystem” of interconnected actors and conditions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Six Components of an Oversight Ecosystem

Such an ecosystem should include at least six components:

- An institutional framework or mandate to ensure public auditors are truly independent and have the resources to do their job;

- High-quality audit reports that cover essential programs and are accessible to the public;

- Effective legislative oversight to respond to audit reports in a timely matter;

- Action by senior government officials to address audit findings and act on audit recommendations;

- Independent follow-up, usually by the SAI or the legislature, to assess whether recommendations have been effectively implemented; and

- Engagement by civil society organizations, the media, and citizens in the audit and oversight process and the discussion of audit findings.

Our new report uses data from IBP’s most recent Open Budget Survey to assesses the strength and adequacy of these six components of oversight ecosystems across 117 countries. The survey data have been converted into scores ranging from 0 to 100 to enable comparisons across countries and the six components. Although the data were compiled before the onset of COVID-19, our report details the state of oversight systems in place as countries began confronting the crisis.

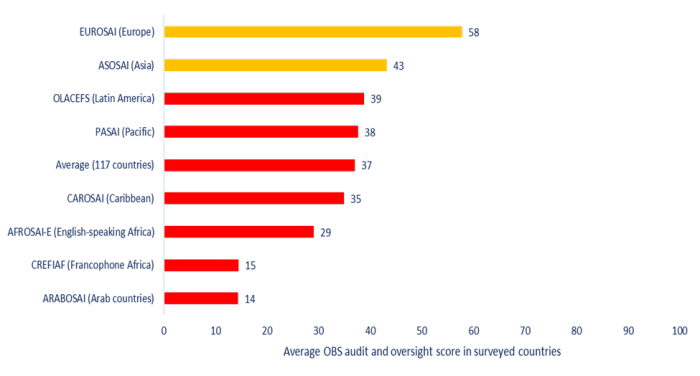

Figure 2: Weak and Inadequate Oversight in all Regions

Figure 2 shows that most countries and all regions of the world suffer from weak or inadequate oversight systems. Generally, regions with more advanced economies receive higher average scores than others, but no region scores higher than 60, which is the benchmark of adequacy using internationally accepted norms for audit and oversight. The weaknesses are most prevalent among countries in the Arab and Francophone African regions.

The global average score on opportunities for public engagement in audit and oversight processes is a dismal 16 out of 100. The implication is that many SAIs and legislative oversight committees are closing their doors to public scrutiny of executed budgets and audit reports. This is a self-defeating mistake as CSOs, the media, and the broader public can be critical allies in bolstering oversight at a time when powerful officials are running roughshod over institutions that are meant to check their actions. Unsurprisingly, the weakest component of oversight is official responses to audit findings, where the global average score is 13 out of 100. This abysmal performance applies to low-, middle- and high-income countries alike.

Recommendations

Now more than ever, countries need to invest in oversight institutions and build rather than undermine their capacity. We hope that our report will serve as a wake-up call to all stakeholders. Immediate steps are needed to preserve the independence of SAIs, enhance public engagement in audit and oversight processes, and improve the review and follow-up of audit reports.

We urge SAIs to make every effort to publish their audit findings and to create meaningful and inclusive mechanisms for civic engagement. This could be achieved by working with civil society groups to improve audit targeting, expand coverage, and enhance capacity.

Legislatures should review and follow-up on audit reports and hold public hearings with in SAIs and the public. They should also ensure that SAIs have the mandate, independence and resources to conduct and publish relevant, high quality audits on the use of emergency funds.

CSOs should follow the example of their counterparts in Ghana to champion the independence of SAIs and call out governments when audit independence is threatened. They should also engage with SAIs in a dialogue on priority and high-risk areas for audit, promote the visibility of audit reports and recommendations, and urge the executive branch to use this information in their fiscal reports.

Donors should explore opportunities for cross-sectoral support to all institutions that form the audit and oversight ecosystem and push back when the independence of SAIs in partner countries is threatened.

Finally, governments should direct audited public organizations to make all information available to auditors, and take appropriate action on audit findings.

This article is part of a series related to the Coronavirus Crisis. All of our articles covering the topic can be found on our PFM Blog Coronavirus Articles page.

[1] Vivek Ramkumar is the Senior Director of Policy and Claire Schouten is the Senior Program Officer, International Advocacy at the International Budget Partnership.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.